The Industrial Revolution

During this unit we will study the following content:

During this unit we will practice the following skills:

- What conditions stimulated the Industrial Revolution.

- Why did Britain become the first industrialized country and how it spread to other parts of the world.

- New ideas / ideologies that emerged as a result.

- Social and political reforms as a reaction to the changes during the Industrial Revolution.

During this unit we will practice the following skills:

- Analyze primary and secondary documents.

- Choose relevant historical sources to support a presentation.

- Analyze the causes and impacts of historical events.

- Write an analytical essay.

The Industrial Revolution as a Marker Event in World History

To be called a Marker Event in world history; a development should qualify in three ways:

Like the Neolithic Revolution that occurred 10,000 years before it, the Industrial Revolution qualifies as a Marker Event according to all of the above criteria. It brought about such sweeping changes that it virtually transformed the world, even areas in which industrialization did not occur. The concept seems simple; invent and perfect machinery to help make human labor more efficient - but that's part of its importance. The change was so basic that it could not help but affect all areas of people's lives in every part of the globe.

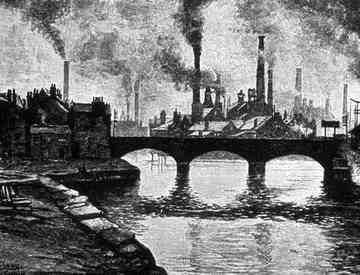

The Industrial Revolution began in England in the late 18th century, and spread during the 19th century to Belgium, Germany, Northern France, the United States, and Japan. Almost all areas of the world felt the effects of the Industrial Revolution because it divided the world into "have" and "have not" countries, with many of the latter being controlled by the former. England's lead in the Industrial Revolution translated into economic prowess and political power that allowed colonization of other lands, eventually building a worldwide British Empire.

- It must cross national or cultural borders, affecting many civilizations.

- Later changes or developments in history must be at least partially traced to this event or series of events.

- It must have impact in other areas. For example, if it is a technological change, it must impact some other major areas, like government, belief systems, social classes, or the economy.

Like the Neolithic Revolution that occurred 10,000 years before it, the Industrial Revolution qualifies as a Marker Event according to all of the above criteria. It brought about such sweeping changes that it virtually transformed the world, even areas in which industrialization did not occur. The concept seems simple; invent and perfect machinery to help make human labor more efficient - but that's part of its importance. The change was so basic that it could not help but affect all areas of people's lives in every part of the globe.

The Industrial Revolution began in England in the late 18th century, and spread during the 19th century to Belgium, Germany, Northern France, the United States, and Japan. Almost all areas of the world felt the effects of the Industrial Revolution because it divided the world into "have" and "have not" countries, with many of the latter being controlled by the former. England's lead in the Industrial Revolution translated into economic prowess and political power that allowed colonization of other lands, eventually building a worldwide British Empire.

Farming before the industrial revoltution

Unit Guide Questions |

Malthus and Brave New World |

|

1. What was the Industrial Revolution/Industrialization? What resources/factors were required for industrialization? (pg. 283-284)

2. Why did the Industrial Revolution begin in Britain? (pg. 284) 3. Describe some of the key inventions in the early Industrial Age. What was the significance of these inventions? (pg. 284-287) 4. How did railroads modernize life in the Industrial Age? (pg. 287-288) 5. What were the effects of industrialization on the living and working conditions of people? Discuss both positive and negative effects. (pg. 289-293) 6. Briefly describe the beginnings of industrialization in the U. S., Belgium, Germany and Japan. (pg. 295-298) 7. Describe the overall impact of industrialization. (pg. 299) 8. How did the philosophies of Adam Smith and David Ricardo support industrialization? (pg. 300-301) 9. Describe the ideas of the following philosophers who challenged the economic system of capitalism: John Mills, Robert Owen and Karl Marx. (pg. 301-304) 10. Describe some of the reforms introduced by governments during the Industrial Revolution? (pg. 304-305 |

|

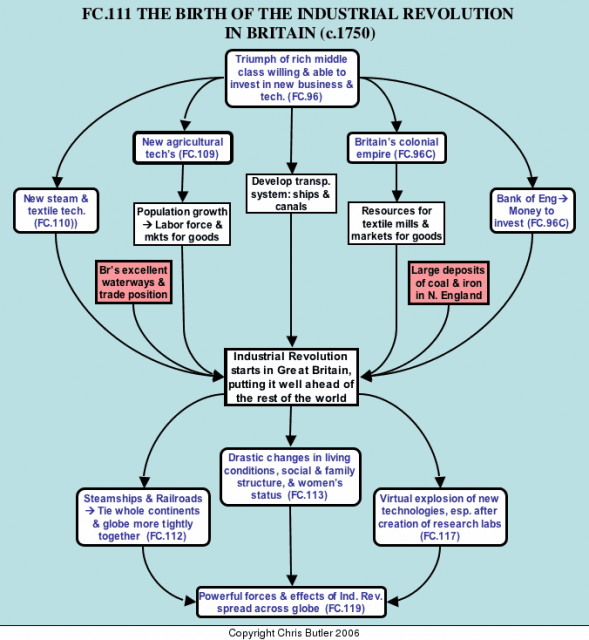

WHY BRITAIN?

The Industrial Revolution helped England greatly increase its output of manufactured goods by substituting hand labor with machine labor. Economic growth in Britain was fueled by a number of factors:

- An Agricultural Revolution - The Industrial Revolution would not have been possible without a series of improvements in agriculture in England. Beginning in the early 1700s, wealthy landowners began to enlarge their farms through enclosure, or fencing or hedging large blocks of land for experiments with new techniques of farming. These scientific farmers improved crop rotation methods, which carefully controlled nutrients in the soil. They bred better livestock, and invented new machines, such as Jethro Tull's seed drill that more effectively planted seeds. The larger the farms and the better the production the fewer farmers were needed. Farmers pushed out of their jobs by enclosure either became tenant farmers or they moved to cities. Better nutrition boosted England's population, creating the first necessary component for the Industrial Revolution: labor.

- A technological revolution - England also was the first to experience a technological revolution, a series of inventions built on the principles of mass production, mechanization, and interchangeable parts.

- Natural resources - Britain had large and accessible supplies of coal and iron - two of the most important raw materials used to produce the goods for the early Industrial Revolution. Also available was water power to fuel the new machines, harbors for its merchant ships, and rivers for inland transportation.

- Economic strength - During the previous era, Britain had already built many of the economic practices and structures necessary for economic expansion, as well as a middle class (the bourgeoisie) that had experience with trading and manufacturing goods. Banks were well established, and they provided loans for businessmen to invest in new machinery and expand their operations.

- Political stability - Britain's political development during this period was fairly stable, with no major internal upheavals occurring. Although Britain took part in many wars during the 1700s, none of them took place on British soil, and its citizens did not seriously question the government's authority. By 1750 Parliament's power far exceeded that of the king, and its members passed laws that protected business and helped expansion.

The Industrial Revolution helped England greatly increase its output of manufactured goods by substituting hand labor with machine labor. Economic growth in Britain was fueled by a number of factors:

- An Agricultural Revolution - The Industrial Revolution would not have been possible without a series of improvements in agriculture in England. Beginning in the early 1700s, wealthy landowners began to enlarge their farms through enclosure, or fencing or hedging large blocks of land for experiments with new techniques of farming. These scientific farmers improved crop rotation methods, which carefully controlled nutrients in the soil. They bred better livestock, and invented new machines, such as Jethro Tull's seed drill that more effectively planted seeds. The larger the farms and the better the production the fewer farmers were needed. Farmers pushed out of their jobs by enclosure either became tenant farmers or they moved to cities. Better nutrition boosted England's population, creating the first necessary component for the Industrial Revolution: labor.

- A technological revolution - England also was the first to experience a technological revolution, a series of inventions built on the principles of mass production, mechanization, and interchangeable parts.

- Natural resources - Britain had large and accessible supplies of coal and iron - two of the most important raw materials used to produce the goods for the early Industrial Revolution. Also available was water power to fuel the new machines, harbors for its merchant ships, and rivers for inland transportation.

- Economic strength - During the previous era, Britain had already built many of the economic practices and structures necessary for economic expansion, as well as a middle class (the bourgeoisie) that had experience with trading and manufacturing goods. Banks were well established, and they provided loans for businessmen to invest in new machinery and expand their operations.

- Political stability - Britain's political development during this period was fairly stable, with no major internal upheavals occurring. Although Britain took part in many wars during the 1700s, none of them took place on British soil, and its citizens did not seriously question the government's authority. By 1750 Parliament's power far exceeded that of the king, and its members passed laws that protected business and helped expansion.

Social, environmental and technological change during the Industrial Revolution

|

|

|

Child Labour |

Life in industrial cities |

Industrial cooking |

|

|

|

|

Pre-industrial football |

The Industrial Revolution and football |

|

|

|

The Spread of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution occurred only in Britain for about 50 years, but it eventually spread to other countries in Europe, the United States, Russia, and Japan. British entrepreneurs and government officials forbade the export of machinery, manufacturing techniques, and skilled workers to other countries but the technologies spread by luring British experts with lucrative offers, and even smuggling secrets into other countries. By the mid-19th century industrialization had spread to France, Germany, Belgium, and the United States.

The earliest center of industrial production in continental Europe was Belgium, where coal, iron, textile, glass, and armaments production flourished. By 1830 French firms had employed many skilled British workers to help establish the textile industry, and railroad lines began to appear across Western Europe. Germany was a little later in developing industry, mainly because no centralized government existed there yet, and a great deal of political unrest made industrialization difficult. However, after the 1840s German coal and iron production skyrocketed, and by the 1850s an extensive rail network was under construction. After German political unification in 1871, the new empire rivaled England in terms of industrial production.

Industrialization began in the United States by the 1820s, delayed until the country had enough laborers and money to invest in business. Both came from Europe, where overpopulation and political revolutions sent immigrants to the United States to seek their fortunes. The American Civil War (1861-1865) delayed further immigration until the 1870s, but it spurred the need for industrial war products, all the way from soldiers' uniforms to guns to railroads for troop transport. Once the war was over, cross-country railroads were built which allowed more people to claim parts of vast inland America and to reach the west coast. The United States had abundant natural resources; land, water, coal and iron ore; and after the great wave of immigration from Europe and Asia in the late 19th century; it also had the labor.

During the late 1800s, industrialization spread to Russia and Japan, in both cases by government initiatives. In Russia the tsarist government encouraged the construction of railroads to link places within the vast reaches of the empire. The most impressive one was the Trans-Siberian line constructed between 1891 and 1904, linking Moscow to Vladivostock on the Pacific Ocean. The railroads also gave Russians access to the empire's many coal and iron deposits, and by 1900 Russia ranked fourth in the world in steel production. The Japanese government also pushed industrialization, hiring thousands of foreign experts to instruct Japanese workers and mangers in the late 1800s. Railroads were constructed, mines were opened, a banking system was organized, and industries were started that produced ships, armaments, silk, cotton, chemicals, and glass. By 1900 Japan was the most industrialized land in Asia, and was set to become a 20th century power.

The earliest center of industrial production in continental Europe was Belgium, where coal, iron, textile, glass, and armaments production flourished. By 1830 French firms had employed many skilled British workers to help establish the textile industry, and railroad lines began to appear across Western Europe. Germany was a little later in developing industry, mainly because no centralized government existed there yet, and a great deal of political unrest made industrialization difficult. However, after the 1840s German coal and iron production skyrocketed, and by the 1850s an extensive rail network was under construction. After German political unification in 1871, the new empire rivaled England in terms of industrial production.

Industrialization began in the United States by the 1820s, delayed until the country had enough laborers and money to invest in business. Both came from Europe, where overpopulation and political revolutions sent immigrants to the United States to seek their fortunes. The American Civil War (1861-1865) delayed further immigration until the 1870s, but it spurred the need for industrial war products, all the way from soldiers' uniforms to guns to railroads for troop transport. Once the war was over, cross-country railroads were built which allowed more people to claim parts of vast inland America and to reach the west coast. The United States had abundant natural resources; land, water, coal and iron ore; and after the great wave of immigration from Europe and Asia in the late 19th century; it also had the labor.

During the late 1800s, industrialization spread to Russia and Japan, in both cases by government initiatives. In Russia the tsarist government encouraged the construction of railroads to link places within the vast reaches of the empire. The most impressive one was the Trans-Siberian line constructed between 1891 and 1904, linking Moscow to Vladivostock on the Pacific Ocean. The railroads also gave Russians access to the empire's many coal and iron deposits, and by 1900 Russia ranked fourth in the world in steel production. The Japanese government also pushed industrialization, hiring thousands of foreign experts to instruct Japanese workers and mangers in the late 1800s. Railroads were constructed, mines were opened, a banking system was organized, and industries were started that produced ships, armaments, silk, cotton, chemicals, and glass. By 1900 Japan was the most industrialized land in Asia, and was set to become a 20th century power.

Reforming the Industrial World

Philosophers of the Industrial Revolution

Important Questions

1. How did the philosophies of Adam Smith and David Ricardo support industrialization? (pg. 300-301)

2. Briefly describe the ideas of the following philosophers who challenged the economic system of capitalism: John Mills, Robert Owen and Karl Marx. (pg. 301-304)

1. How did the philosophies of Adam Smith and David Ricardo support industrialization? (pg. 300-301)

2. Briefly describe the ideas of the following philosophers who challenged the economic system of capitalism: John Mills, Robert Owen and Karl Marx. (pg. 301-304)

CHANGES IN SOCIAL CLASSES

A major social change brought about by the Industrial Revolution was the development of a relatively large middle class, or "bourgeoisie" in industrialized countries. This class had been growing in Europe since medieval days when wealth was based on land, and most people were peasants. With the advent of industrialization, wealth was increasingly based on money and success in business enterprises, although the status of inherited titles of nobility based on land ownership remained in place. However, land had never produced such riches as did business enterprises of this era, and so members of the bourgeoisie were the wealthiest people around.

However, most members of the middle class were not wealthy, owning small businesses or serving as managers or administrators in large businesses. They generally had comfortable lifestyles, and many were concerned with respectability, or the demonstration that they were of a higher social class than factory workers were. They valued the hard work, ambition, and individual responsibility that had led to their own success, and many believed that the lower classes only had themselves to blame for their failures. This attitude generally extended not to just the urban poor, but to people who still farmed in rural areas.

The urban poor were often at the mercy of business cycles; swings between economic hard times to recovery and growth. Factory workers were laid off from their jobs during hard times, making their lives even more difficult. With this recurrent unemployment came public behaviors, such as drunkenness and fighting, that appalled the middle class, who stressed sobriety, thrift, industriousness, and responsibility.

Social class distinctions were reinforced by Social Darwinism, a philosophy by Englishman Herbert Spencer. He argued that human society operates by a system of natural selection, whereby individuals and ways of life automatically gravitate to their proper station. According to Social Darwinists, poverty was a "natural condition" for inferior individuals.

GENDER ROLES AND INEQUALITY

Changes in gender roles generally fell along class lines, with relationships between men and women of the middle class being very different from those in the lower classes.

LOWER CLASS MEN AND WOMEN

Factory workers often resisted the work discipline and pressures imposed by their middle class bosses. They worked long hours in unfulfilling jobs, but their leisure time interests fed the popularity of two sports: European soccer and American baseball. They also did less respectable things, like socializing at bars and pubs, staging dog or chicken fights, and participating in other activities that middle class men disdained.

Meanwhile, most of their wives were working, most commonly as domestic servants for middle class households, jobs that they usually preferred to factory work. Young women in rural areas often came to cities or suburban areas to work as house servants. They often sent some of their wages home to support their families in the country, and some saved dowry money. Others saved to support ambitions to become clerks or secretaries, jobs increasingly filled by women, but supervised by men.

MIDDLE CLASS MEN AND WOMEN

When production moved outside the home, men who became owners or managers of factories gained status. Industrial work kept the economy moving, and it was valued more than the domestic chores traditionally carried out by women. Men's wages supported the families, since they usually were the ones who made their comfortable life styles possible. The work ethic of the middle class infiltrated leisure time as well. Many were intent on self-improvement, reading books or attending lectures on business or culture. Many factory owners and managers stressed the importance of church attendance for all, hoping that factory workers could be persuaded to adopt middle-class values of respectability.

Middle class women generally did not work outside of the home, partly because men came to see stay-at-home wives as a symbol of their success. What followed was a "cult of domesticity" that justified removing women from the work place. Instead, they filled their lives with the care of children and the operation of their homes. Since most middle-class women had servants, they spent time supervising them, but they also had to do fewer household chores themselves.

Historians disagree in their answers to the question of whether or not gender inequality grew because of industrialization. Gender roles were generally fixed in agricultural societies, and if the lives of working class people in industrial societies are examined, it is difficult to see that any significant changes in the gender gap took place at all. However, middle class gender roles provide the real basis for the argument. On the one hand, some argue that women were forced out of many areas of meaningful work, isolated in their homes to obsess about issues of marginal importance. On the farm, their work was "women's work," but they were an integral part of the central enterprise of their time: agriculture. Their work in raising children was vital to the economy, but industrialization rendered children superfluous as well, whose only role was to grow up safely enough to fill their adult gender-related duties. On the other hand, the "cult of domesticity" included a sort of idolizing of women that made them responsible for moral values and standards. Women were seen as stable and pure, the vision of what kept their men devoted to the tasks of running the economy. Women as standard-setters, then, became the important force in shaping children to value respectability, lead moral lives, and be responsible for their own behaviors. Without women filling this important role, the entire social structure that supported industrialized power would collapse.

A major social change brought about by the Industrial Revolution was the development of a relatively large middle class, or "bourgeoisie" in industrialized countries. This class had been growing in Europe since medieval days when wealth was based on land, and most people were peasants. With the advent of industrialization, wealth was increasingly based on money and success in business enterprises, although the status of inherited titles of nobility based on land ownership remained in place. However, land had never produced such riches as did business enterprises of this era, and so members of the bourgeoisie were the wealthiest people around.

However, most members of the middle class were not wealthy, owning small businesses or serving as managers or administrators in large businesses. They generally had comfortable lifestyles, and many were concerned with respectability, or the demonstration that they were of a higher social class than factory workers were. They valued the hard work, ambition, and individual responsibility that had led to their own success, and many believed that the lower classes only had themselves to blame for their failures. This attitude generally extended not to just the urban poor, but to people who still farmed in rural areas.

The urban poor were often at the mercy of business cycles; swings between economic hard times to recovery and growth. Factory workers were laid off from their jobs during hard times, making their lives even more difficult. With this recurrent unemployment came public behaviors, such as drunkenness and fighting, that appalled the middle class, who stressed sobriety, thrift, industriousness, and responsibility.

Social class distinctions were reinforced by Social Darwinism, a philosophy by Englishman Herbert Spencer. He argued that human society operates by a system of natural selection, whereby individuals and ways of life automatically gravitate to their proper station. According to Social Darwinists, poverty was a "natural condition" for inferior individuals.

GENDER ROLES AND INEQUALITY

Changes in gender roles generally fell along class lines, with relationships between men and women of the middle class being very different from those in the lower classes.

LOWER CLASS MEN AND WOMEN

Factory workers often resisted the work discipline and pressures imposed by their middle class bosses. They worked long hours in unfulfilling jobs, but their leisure time interests fed the popularity of two sports: European soccer and American baseball. They also did less respectable things, like socializing at bars and pubs, staging dog or chicken fights, and participating in other activities that middle class men disdained.

Meanwhile, most of their wives were working, most commonly as domestic servants for middle class households, jobs that they usually preferred to factory work. Young women in rural areas often came to cities or suburban areas to work as house servants. They often sent some of their wages home to support their families in the country, and some saved dowry money. Others saved to support ambitions to become clerks or secretaries, jobs increasingly filled by women, but supervised by men.

MIDDLE CLASS MEN AND WOMEN

When production moved outside the home, men who became owners or managers of factories gained status. Industrial work kept the economy moving, and it was valued more than the domestic chores traditionally carried out by women. Men's wages supported the families, since they usually were the ones who made their comfortable life styles possible. The work ethic of the middle class infiltrated leisure time as well. Many were intent on self-improvement, reading books or attending lectures on business or culture. Many factory owners and managers stressed the importance of church attendance for all, hoping that factory workers could be persuaded to adopt middle-class values of respectability.

Middle class women generally did not work outside of the home, partly because men came to see stay-at-home wives as a symbol of their success. What followed was a "cult of domesticity" that justified removing women from the work place. Instead, they filled their lives with the care of children and the operation of their homes. Since most middle-class women had servants, they spent time supervising them, but they also had to do fewer household chores themselves.

Historians disagree in their answers to the question of whether or not gender inequality grew because of industrialization. Gender roles were generally fixed in agricultural societies, and if the lives of working class people in industrial societies are examined, it is difficult to see that any significant changes in the gender gap took place at all. However, middle class gender roles provide the real basis for the argument. On the one hand, some argue that women were forced out of many areas of meaningful work, isolated in their homes to obsess about issues of marginal importance. On the farm, their work was "women's work," but they were an integral part of the central enterprise of their time: agriculture. Their work in raising children was vital to the economy, but industrialization rendered children superfluous as well, whose only role was to grow up safely enough to fill their adult gender-related duties. On the other hand, the "cult of domesticity" included a sort of idolizing of women that made them responsible for moral values and standards. Women were seen as stable and pure, the vision of what kept their men devoted to the tasks of running the economy. Women as standard-setters, then, became the important force in shaping children to value respectability, lead moral lives, and be responsible for their own behaviors. Without women filling this important role, the entire social structure that supported industrialized power would collapse.