2.1 The functions and evolution of human resource management

What we will study?

- Identify the constraints and opportunities presented by demographic change

- Discuss the significance of labour mobility

- Analyse the workforce planning process

- Evaluate strategies for developing future human resources

- Discuss different methods of recruitment, training, appraisal and dismissal

- Describe reasons for and consequences of changing work patterns and practices

- Analyse the impact on business of legal employment rights HL

- Examine how recruitment, training and appraisal can help achieve workforce planning targets

- Analyse the consequences of changing work patterns and practices on business

- Apply Handy's Shamrock organisation theory

What is Human Resource Management?

Human Resource Management ("HRM") is a way of management that links people-related activities to the strategy of a business or organization. It has several goals:

- To meet the needs of the business and management (rather than just serve the interests of employees)

- To link human resource strategies / policies to the business goals and objectives

- To find ways for human resources to "add value" to a business

- To help a business gain the commitment of employees to its values, goals and objectives

Human Resource Management ("HRM") is a way of management that links people-related activities to the strategy of a business or organization. It has several goals:

- To meet the needs of the business and management (rather than just serve the interests of employees)

- To link human resource strategies / policies to the business goals and objectives

- To find ways for human resources to "add value" to a business

- To help a business gain the commitment of employees to its values, goals and objectives

What is workforce planning?

Put simply workforce planning involves two main stages; forecasting the number of staff required and forecasting the skills required. Forecasting the number of staff needed by a business will depend on things like:

Forecasting required skills would depend on things things such as technological change or if your business has the need for a flexible or multi-skilled staff. Seisen is a relatively small school where most teachers teach both middle and high school, in larger schools teachers will only Grade 10 English for example.

- The anticipated demand for the firm's product - a greeting card company would be able to forecast that it might need extra staff around holiday periods such as Christmas

- The productivity levels of staff - if productivity is low then more staff may be needed

- The objectives of the business - if the business decides to expand or streamline production

- Labour turnover and absenteeism - a high labour turnover would mean a need for more manpower

Forecasting required skills would depend on things things such as technological change or if your business has the need for a flexible or multi-skilled staff. Seisen is a relatively small school where most teachers teach both middle and high school, in larger schools teachers will only Grade 10 English for example.

Recruitment

|

Without the right staff with the right skills, a business cannot make enough products to satisfy customer requirements. This is why organizations draw up workforce plans to identify their future staffing requirements. For example, they may develop plans to recruit a new IT Manager when the current one plans to retire in eight months time.

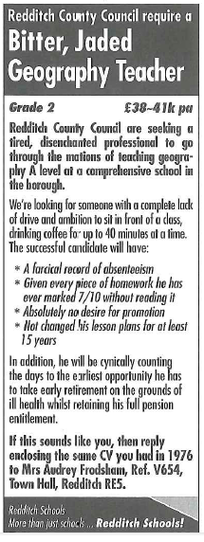

Recruitment is the process by which a business seeks to hire the right person for a vacancy. The firm writes a job description and person specification for the post and then advertises the vacancy in an appropriate place. What makes for an effective job advertisement? 1. Truthful – Does not include incorrect or mis-leading information. 2. Concise – Attracts the interest of suitable candidates without over-loading them with details. 3. Targeted – Simply states the key parts of the job description and person specification to ensure that only suitable people apply. 4. Positive – Encourages suitable applicants to apply. 5. Contact details – Clearly states how & to whom prospective applicants should apply. |

Demographic change

Demographic change: Changes in the size, structure and distribution of populations over time and place. The potential supply of labour to any organisation is affected by demographic changes.

How not to do a staff appraisal

Changing work patterns and practices

The following article appeared in The Economist on January 3rd 2015. It is an excellent, and up-to-date example of how work patterns and practices are changing in the 21st Century,

The on-demand economy: Workers on tap

The rise of the on-demand economy poses difficult questions for workers, companies and politicians.

IN THE early 20th century Henry Ford combined moving assembly lines with mass labour to make building cars much cheaper and quicker—thus turning the automobile from a rich man’s toy into transport for the masses. Today a growing group of entrepreneurs is striving to do the same to services, bringing together computer power with freelance workers to supply luxuries that were once reserved for the wealthy. Uber provides chauffeurs. Handy supplies cleaners. SpoonRocket delivers restaurant meals to your door. Instacart keeps your fridge stocked. In San Francisco a young computer programmer can already live like a princess.

Yet this on-demand economy goes much wider than the occasional luxury. Click on Medicast’s app, and a doctor will be knocking on your door within two hours. Want a lawyer or a consultant? Axiom will supply the former, Eden McCallum the latter. Other companies offer prizes to freelances to solve R&D problems or to come up with advertising ideas. And a growing number of agencies are delivering freelances of all sorts, such as Freelancer.com and Elance-oDesk, which links up 9.3m workers for hire with 3.7m companies.

The on-demand economy is small, but it is growing quickly (see article). Uber, founded in San Francisco in 2009, now operates in 53 countries, had sales exceeding $1 billion in 2014 and a valuation of $40 billion. Like the moving assembly line, the idea of connecting people with freelances to solve their problems sounds simple. But, like mass production, it has profound implications for everything from the organisation of work to the nature of the social contract in a capitalist society.

Baby, you can drive my car—and stock my fridge

Some of the forces behind the on-demand economy have been around for decades. Ever since the 1970s the economy that Henry Ford helped create, with big firms and big trade unions, has withered. Manufacturing jobs have been automated out of existence or outsourced abroad, while big companies have abandoned lifetime employment. Some 53m American workers already work as freelances.

But two powerful forces are speeding this up and pushing it into ever more parts of the economy. The first is technology. Cheap computing power means a lone thespian with an Apple Mac can create videos that rival those of Hollywood studios. Complex tasks, such as programming a computer or writing a legal brief, can now be divided into their component parts—and subcontracted to specialists around the world. The on-demand economy allows society to tap into its under-used resources: thus Uber gets people to rent their own cars, and InnoCentive lets them rent their spare brain capacity.

The other great force is changing social habits. Karl Marx said that the world would be divided into people who owned the means of production—the idle rich—and people who worked for them. In fact it is increasingly being divided between people who have money but no time and people who have time but no money. The on-demand economy provides a way for these two groups to trade with each other.

This will push service companies to follow manufacturers and focus on their core competencies. The “transaction cost” of using an outsider to fix something (as opposed to keeping that function within your company) is falling. Rather than controlling fixed resources, on-demand companies are middle-men, arranging connections and overseeing quality. They don’t employ full-time lawyers and accountants with guaranteed pay and benefits. Uber drivers get paid only when they work and are responsible for their own pensions and health care. Risks borne by companies are being pushed back on to individuals—and that has consequences for everybody.

Obamacare and Brand You

The on-demand economy is already provoking political debate, with Uber at the centre of much of it. Many cities, states and countries have banned the ride-sharing company on safety or regulatory grounds. Taxi drivers have staged protests against it. Uber drivers have gone on strike, demanding better benefits. Techno-optimists dismiss all this as teething trouble: the on-demand economy gives consumers greater choice, they argue, while letting people work whenever they want. Society gains because idle resources are put to use. Most of Uber’s cars would otherwise be parked in the garage.

The truth is more nuanced. Consumers are clear winners; so are Western workers who value flexibility over security, such as women who want to combine work with child-rearing. Taxpayers stand to gain if on-demand labour is used to improve efficiency in the provision of public services. But workers who value security over flexibility, including a lot of middle-aged lawyers, doctors and taxi drivers, feel justifiably threatened. And the on-demand economy certainly produces unfairnesses: taxpayers will also end up supporting many contract workers who have never built up pensions.

This sense of nuance should inform policymaking. Governments that outlaw on-demand firms are simply handicapping the rest of their economies. But that does not mean they should sit on their hands. The ways governments measure employment and wages will have to change. Many European tax systems treat freelances as second-class citizens, while American states have different rules for “contract workers” that could be tidied up. Too much of the welfare state is delivered through employers, especially pensions and health care: both should be tied to the individual and made portable, one area where Obamacare was a big step forward.

But even if governments adjust their policies to a more individualistic age, the on-demand economy clearly imposes more risk on individuals. People will have to master multiple skills if they are to survive in such a world—and keep those skills up to date. Professional sorts in big service firms will have to take more responsibility for educating themselves. People will also have to learn how to sell themselves, through personal networking and social media or, if they are really ambitious, turning themselves into brands. In a more fluid world, everybody will need to learn how to manage You Inc.

Jan 3rd 2015 | From the print edition

The on-demand economy: Workers on tap

The rise of the on-demand economy poses difficult questions for workers, companies and politicians.

IN THE early 20th century Henry Ford combined moving assembly lines with mass labour to make building cars much cheaper and quicker—thus turning the automobile from a rich man’s toy into transport for the masses. Today a growing group of entrepreneurs is striving to do the same to services, bringing together computer power with freelance workers to supply luxuries that were once reserved for the wealthy. Uber provides chauffeurs. Handy supplies cleaners. SpoonRocket delivers restaurant meals to your door. Instacart keeps your fridge stocked. In San Francisco a young computer programmer can already live like a princess.

Yet this on-demand economy goes much wider than the occasional luxury. Click on Medicast’s app, and a doctor will be knocking on your door within two hours. Want a lawyer or a consultant? Axiom will supply the former, Eden McCallum the latter. Other companies offer prizes to freelances to solve R&D problems or to come up with advertising ideas. And a growing number of agencies are delivering freelances of all sorts, such as Freelancer.com and Elance-oDesk, which links up 9.3m workers for hire with 3.7m companies.

The on-demand economy is small, but it is growing quickly (see article). Uber, founded in San Francisco in 2009, now operates in 53 countries, had sales exceeding $1 billion in 2014 and a valuation of $40 billion. Like the moving assembly line, the idea of connecting people with freelances to solve their problems sounds simple. But, like mass production, it has profound implications for everything from the organisation of work to the nature of the social contract in a capitalist society.

Baby, you can drive my car—and stock my fridge

Some of the forces behind the on-demand economy have been around for decades. Ever since the 1970s the economy that Henry Ford helped create, with big firms and big trade unions, has withered. Manufacturing jobs have been automated out of existence or outsourced abroad, while big companies have abandoned lifetime employment. Some 53m American workers already work as freelances.

But two powerful forces are speeding this up and pushing it into ever more parts of the economy. The first is technology. Cheap computing power means a lone thespian with an Apple Mac can create videos that rival those of Hollywood studios. Complex tasks, such as programming a computer or writing a legal brief, can now be divided into their component parts—and subcontracted to specialists around the world. The on-demand economy allows society to tap into its under-used resources: thus Uber gets people to rent their own cars, and InnoCentive lets them rent their spare brain capacity.

The other great force is changing social habits. Karl Marx said that the world would be divided into people who owned the means of production—the idle rich—and people who worked for them. In fact it is increasingly being divided between people who have money but no time and people who have time but no money. The on-demand economy provides a way for these two groups to trade with each other.

This will push service companies to follow manufacturers and focus on their core competencies. The “transaction cost” of using an outsider to fix something (as opposed to keeping that function within your company) is falling. Rather than controlling fixed resources, on-demand companies are middle-men, arranging connections and overseeing quality. They don’t employ full-time lawyers and accountants with guaranteed pay and benefits. Uber drivers get paid only when they work and are responsible for their own pensions and health care. Risks borne by companies are being pushed back on to individuals—and that has consequences for everybody.

Obamacare and Brand You

The on-demand economy is already provoking political debate, with Uber at the centre of much of it. Many cities, states and countries have banned the ride-sharing company on safety or regulatory grounds. Taxi drivers have staged protests against it. Uber drivers have gone on strike, demanding better benefits. Techno-optimists dismiss all this as teething trouble: the on-demand economy gives consumers greater choice, they argue, while letting people work whenever they want. Society gains because idle resources are put to use. Most of Uber’s cars would otherwise be parked in the garage.

The truth is more nuanced. Consumers are clear winners; so are Western workers who value flexibility over security, such as women who want to combine work with child-rearing. Taxpayers stand to gain if on-demand labour is used to improve efficiency in the provision of public services. But workers who value security over flexibility, including a lot of middle-aged lawyers, doctors and taxi drivers, feel justifiably threatened. And the on-demand economy certainly produces unfairnesses: taxpayers will also end up supporting many contract workers who have never built up pensions.

This sense of nuance should inform policymaking. Governments that outlaw on-demand firms are simply handicapping the rest of their economies. But that does not mean they should sit on their hands. The ways governments measure employment and wages will have to change. Many European tax systems treat freelances as second-class citizens, while American states have different rules for “contract workers” that could be tidied up. Too much of the welfare state is delivered through employers, especially pensions and health care: both should be tied to the individual and made portable, one area where Obamacare was a big step forward.

But even if governments adjust their policies to a more individualistic age, the on-demand economy clearly imposes more risk on individuals. People will have to master multiple skills if they are to survive in such a world—and keep those skills up to date. Professional sorts in big service firms will have to take more responsibility for educating themselves. People will also have to learn how to sell themselves, through personal networking and social media or, if they are really ambitious, turning themselves into brands. In a more fluid world, everybody will need to learn how to manage You Inc.

Jan 3rd 2015 | From the print edition

Taking into account cultural differences when doing business

|

|

|